Citado por: 1

"[...] In the Gallaretese [sic] neighborhood in Milan, to the moderated expressionism of Carlo Aymonino, who articulates his residential blocks as they converge into the fulcrum of the open-air theater in a complex play of artificial streets and nodes [...], Rossi creates an opposition in the sacred precision of his geometric block which is held above ideology and above all utopian proposals for a ‘new lifestyle.'

The complex as designed by Aymonino wishes to underscore every resolution, every joint, every formal artifice. Aymonino apparently wants to speak the language of superimposition and complexity, within which single objects violently strung together insist upon displaying their individual role within the entire ‘machine.' Yet, and quite significantly, Aymonino, by assigning to Rossi the design for one of the blocks within this neighborhood [...], must have felt the need to confront himself with a proposal radically opposed to his own. And it is here that we find, facing the aggregation of Aymonino's signs, the absolute sign of Rossi." [p. 45-46]

TAFURI, Manfredo. L'architecture dans le boudoir: the language of criticism and the criticism of language. Oppositions, Nova York, n. 3, p. 37-62, mai. 1974.

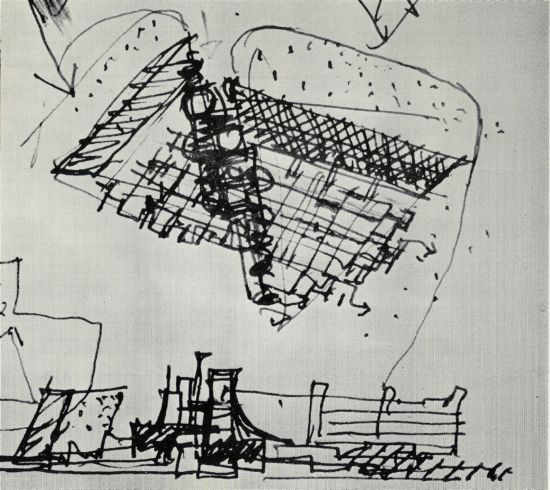

"In my design for the residential block in the Gallaratese district of Milan there is an analogical relationship with certain engineering works that mix freely with both the corridor typology and a related feeling I have always experienced in the architecture of the traditional Milanese tenements, where the corridor signifies a life-style bathed in everyday occurrences, domestic intimacy, and varied personal relationships. However, another aspect of this design was made clear to me by Fabio Reinhart driving through the San Bernardino Pass, as we often did, in order to reach Zurich from the Ticino Valley; Reinhart noticed the repetitive element in the system of open-sided tunnels, and therefore the inherent pattern. I understood on another occasion how I must have been conscious of that particular structure - and not only of the forms - of the gallery, or covered passage, without necessarily intending to express it in a work of architecture.

In like fashion I could put together an album relating to my designs and consisting only of things already seen in other places: galleries, silos, old houses, factories, farm-houses in the Lombard countryside or near Berlin, and many more - something between memory and an inventory.

I do not believe that these designs are leading away from the rationalist position that I have always upheld; perhaps it is only that I see certain problems in a more comprehensive way now.

In any case I am increasingly convinced of what I wrote several years ago in the ‘Introduction to Boullée': that in order to study the irrational it is necessary somehow to take up a rational position as observer.

Otherwise, observation - and eventually participation - give way to disorder." [p. 350]

ROSSI, Aldo. An analogical architecture. In: NESBITT, Kate (Ed.). Theorizing a new agenda for architecture: an anthology of architectural theory, 1965-1995. Nova York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996. p. 348-352, grifo do autor.

"Aldo Rossi and the Italian Rationalists try very sympathetically to continue the classical patterns of Italian cities, designing neutral buildings which have a ‘zero degree' of historical association ; but their work invariably recalls the Fascist architecture of the thirties - despite countless disclaimers. The semantic overtones are again erratic, and focus on such oppressive meanings, because the building is oversimplified and monotonous. Serious critics and apologists for them, such as Manfredo Tafuri, find themselves evading the obvious in their attempt to justify such buildings with elaborate, esoteric interpretation." [p. 20]

JENCKS, Charles. The language of post-modern architecture. Nova York: Rizzoli, 1977.

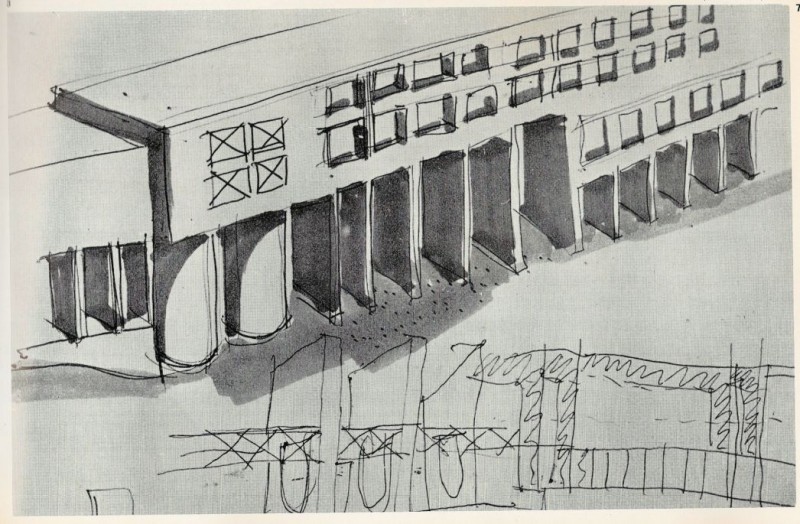

"[...] Aware of the tendency of interested rationality to absorb and distort every significant cultural gesture, Rossi structured his work about historical architectonic elements that could recall and yet transcend the rational if arbitrary paradigms of the Enlightenment; the pure form postulated in the second half of the 18th century by Piranesi, Ledoux, Boullée and Lequeu. The most enigmatic, not to say hermetic, aspect of his thought resides in his unstated preoccupation with the Panopticon (cf. Michel Foucault's Surveiller et punir of 1975) under the rubric of which he would surely include - after Puqin's Contrasts of 1843 - the school, the hospital and the prison. Rossi seems to have obsessively returned to these regulatory, quasi-punitive, institutions which for him, in conjunction with the monument and cemetery, constitute the only programmes capable of embodying the values of architecture per se. After the thesis that Loos first set out in his essay Architektur of 1910, Rossi has recognized that most modern programmes are inappropriate vehicles for architecture and for him this has meant having recourse to a so-called analogical architecture whose referents and elements are to be abstracted from the vernacular, in the broadest possible sense. To this end his Gallaratese apartment block, designed as part of Carlo Aymonino's housing complex built on the outskirts of Milan in 1973, was an occasion to evoke the architecture of the traditional Milanese tenement. Similarly his town hall for Trieste, projected in the form of a penitentiary in 1973, was both a homage to the local 19th-century building tradition and a sardonic comment on the ultimate nature of modern bureaucracy. [...]" [p. 294-295]

FRAMPTON, Kenneth. Modern architecture: a critical history. Londres: Thames & Hudson, 1980, grifos do autor.

"The houses of the dead and those of childhood, the theater or the house of representation - all these projects and buildings seem to me to embrace the seasons and ages of life. Yet they no more represent themes than functions; rather they are the forms in which life, and therefore death, are manifested.

I could speak in this sense of still other projects which I have so far barely touched upon, projects like the housing block at San Rocco and that for the Gallaratese quarter in Milan. The first dates back to 1966; the second to 1969-1970. Concerning the former I have mentioned only the superimposition of the Roman grid and the subsequent shifting of this grid, creating an effect like the accidental crack in a mirror. Concerning the latter, I have mentioned its size and simplicity, in the sense of a rigorous technology.

Yet in speaking of the forms in which human life is manifested, I ought to elaborate further on some of those structures with which this sense of life has been associated for me and which have impressed me from an archaeological and anthropological point of view ever since my early youth. I have mentioned the corrales of Seville, the courtyards of Milan, in particular the courtyard of the Hotel Sirena; and the balconies, arcades, corridors, as well as the literary and actual impressions made on me by convents, schools, barracks. In a word, those forms of dwelling - together with that of the villa - are stored in the history of man to such a degree that they belong as much to anthropology as to architecture. It is difficult to imagine other forms, other geometric representations, precisely because we do not already have examples of them." [p. 69-71]

ROSSI, Aldo. A scientific autobiography. Cambridge; Londres: The MIT Press, 1981, grifo do autor.

"Fascism haunts the colonnade of the Gallaratese project, but it is only one of the ghosts. Every classical architect from Le Corbusier to Ledoux and Ictinos is lurking behind the piers. All of Italy is there in public grandeur and private poverty and indomitable rhetorical stance. An American cannot fail to guess that Louis Kahn is also present. His majestic drawing of the hypostyle hall at Karnak - where the columns are neither structurally muscular nor sculpturally active but simply enormously there, modeling the light, taking up space - seems almost prototypical of Rossi's colossal columns here. These are so big in relation to their modest load that there seems to be no structural compression upon them and they remain purely visual beings, apparitions stepping forward among the flat piers. Whatever the case, the colonnade of the Gallaratese is the ultimate space of dream. Judged by the functionalist criteria of modernist criticism it might be seen as over-scaled and gratuitous, but it must in fact be seen literally in another light, in that of Rossi's ‘unforeseeable functions.' And there, however relegated to the edges of consciousness, its shapes march through the corridors of sleep and populate dreams. It is only fair to Freud to note that there may well be a sexual element in this as well, since the long, taut shape of Rossi's slab is clearly read as a body intruding into Aymonino's brown, ebullient, L-shaped building. Whatever the reasons, and they are surely many, something deep is touched, some need of the soul for space and grandeur, for glory, love, and connection, some generous wish not verbalized but pictorially represented here." [p. 114]

SCULLY, Vincent. Postscript: ideology in form. In: ROSSI, Aldo. A scientific autobiography. Cambridge; Londres: The MIT Press, 1981. p. 111-116.

"If [Giancarlo] De Carlo was responsible for developing the idea of broader participation in the design process in Italy, looking to generate architecture as the outcome of a democratic dialogue with the working class, the Gallaratese 2 housing complex in Milan designed by Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi in the same period represented an opposing design approach, looking for the autonomy of architecture as a plastic, ideological, contemporary monument which could ‘save' Italy's peripheral areas." [p. 269]

"As with the Matteotti Village in Terni, Gallaratese 2 failed as a social and urban alternative model. Once completed in 1972, Monte Amiata tried to sell it off to the municipality of Milan, and then in 1974 decided to sell the dwellings at a reduced price to enable lower income earners to become home owners. In the same year, groups of students and workers occupied the buildings until they were forcibly removed by the police. Most of the commercial and public uses envisaged for some of the units failed, and after a few years, home owners decided to gate the housing complex, thwarting the idea of Gallaratese 2 as an active fragment of a new, emerging city." [p. 271-274]

MOLINARI, Luca. Matteotti Village and Gallaratese 2: design criticism of the Italian Welfare State. In: SWENARTON, Mark; AVERMAETE, Tom; DEN HEUVEL, Dirk (Ed.). Architecture and the Welfare State. Londres; Nova York: Routledge, 2015. p. 259-275.

Projeto

Projeto Publicação

Publicação Evento

Evento Fato Relevante

Fato Relevante